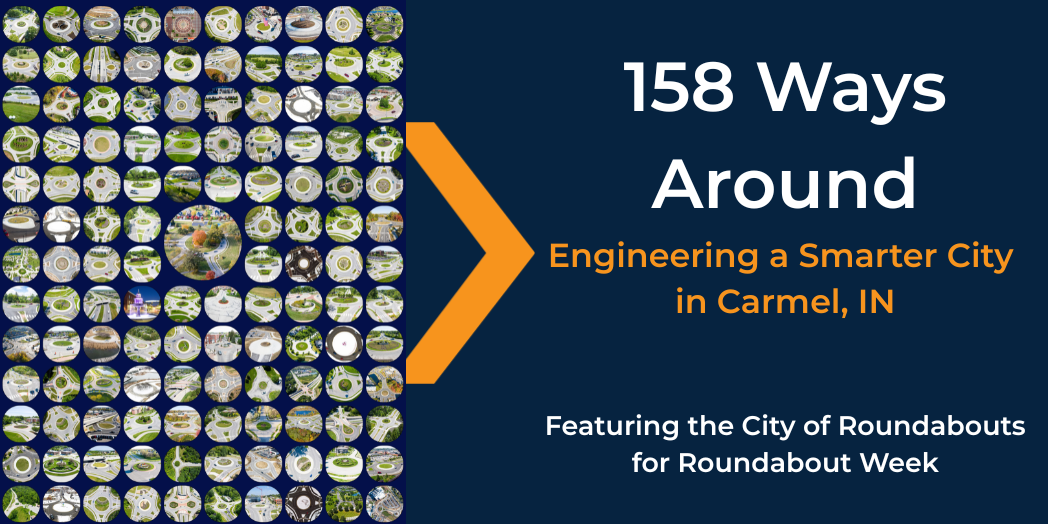

“Carmel worked really hard for a long time not to be a single signal town. And for the last 30 years, we’ve worked really hard to get back to a single signal town.”

That’s how Bradley Pease, PE, the Director of Engineering for Carmel, Indiana, describes the City of Roundabouts. Once a town defined by a single signalized intersection, Carmel has grown into a model of safety and mobility through its roundabout network.

From One Signal to a Roundabout Capital

Carmel’s transformation begins not with a roundabout, but with a traffic light. At Main Street and Range Line Road, Carmel installed what is widely recognized as Indiana’s first automated traffic signal, now commemorated by a historic marker. For decades, Carmel was known as a “one-signal town.”

116th Street and Towne Road Roundabout

In the late 1990s, Carmel turned the corner, trading signals for roundabouts. In 1997, Carmel opened its first roundabout at Main Street and River Road, championed by newly elected Mayor James Brainard. Having studied abroad in Europe, he’d seen how modern roundabouts improved safety and efficiency. Back home, he dug into research at the Purdue University library to demonstrate how the approach could benefit Carmel. Early roundabout projects faced skepticism, but as they were completed, results came back: fewer crashes, smoother traffic, and safer conditions for all users. Support grew, and one roundabout became many. Today, Carmel leads the nation with 158 roundabouts.

A Conversation with Bradley Pease, PE – Director of Engineering

We sat down with Bradley Pease to talk through Carmel’s rise to “Roundabout Capital of the U.S.,” the engineering challenges and benefits of the roundabout network, and how the city continues to prioritize safety, connectivity, and design innovation. Pease joined the city in 2015 when the program stood at 91 roundabouts and counting.

Crash Trends and Safety Impacts of Carmel’s Roundabouts

According to the City of Carmel, injury crashes have declined by about 80% and overall crashes by roughly 40% on roadways converted to roundabouts. These reductions apply throughout the network, including at more complex designs like the double-teardrop roundabouts on Keystone Parkway, where peer-reviewed research has found 84% fewer injury crashes and 63% fewer total crashes. Roundabouts also reduce idling at former signalized intersections, supporting lower emissions and fuel use across daily trips.

Taken together, these aren’t isolated wins; they reflect a network effect. “It’s not just about one intersection,” Pease explained. “It’s about how the network changes the way people drive and how safe everyone feels using our streets.”

The Power of a Roundabout Network

While each conversion improves a single intersection, Carmel’s real advantage comes from scale. With roundabouts at nearly every major crossing, drivers adjust their behavior and approach speeds more slowly, conflict points are reduced, and travel becomes more predictable. Families walking to schools and parks find more consistent, safer crossings; cyclists benefit from clearer decision points; and the city’s operations prove more resilient during storms or power outages without reliance on signals. Fewer stops and less idling also mean lower emissions and delay day to day.

“When you get to a critical mass [of roundabouts], it changes your driving behavior.”

Designing for People: Landscaping, Lighting, Art, and Multi-Modal Access

What sets Carmel’s roundabouts apart is the attention to how each is experienced, not just how it performs.

- Landscaping and lighting are placed to guide sightlines and driver focus while improving nighttime visibility at crossings.

- Public art transforms many roundabouts into civic landmarks that aid wayfinding and reflect community identity.

- Pedestrian and cyclist safety is built in raised crosswalks, beacons, refuge islands, and multi-use path connections create predictable, protected routes.

- Emergency response is always considered. Geometries, crosswalk features, and clear zones are balanced so fire and police can maneuver quickly without compromising everyday safety.

Clark Dietz Contributions

106th Street and Towne Road Roundabout drone image

Clark Dietz has partnered with Carmel on two significant conversions, each replacing a signalized intersection with a safer, more connected roundabout.

- 106th Street and Towne Road – Formerly a four-legged signal, now a two-lane, four-approach roundabout sized for corridor growth. Pedestrian walkways and crossings on every approach improve comfort and connectivity for people walking and biking. RODEL modeling refined the geometry, while utility coordination and pavement-reuse strategies kept the project efficient and cost-conscious.

116th Street and Towne Road Roundabout drone image

- 116th Street and Towne Road – Another two-lane, four-approach roundabout replaced a busy signal. With Towne Meadow Elementary to the south and Coxhall Gardens to the north, the design prioritized people—marked crosswalks with flashing beacons on each approach support safer, more visible crossings. The team reused existing storm sewer trunk lines to control costs, and RODEL modeling optimized the geometry to improve flow while minimizing pavement.

These projects show how thoughtful engineering, modeling, coordination, and user-focused design create roundabouts that serve drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists alike.

Evolving Design and Lessons Learned

Carmel’s program spans nearly three decades, and designs have evolved. Early roundabouts on Hazel Dell Parkway drew from more radial, European-style layouts; while functional, some weren’t as intuitive for U.S. drivers and were later retrofitted to align with updated standards and volumes. Over time, a durable playbook emerged:

- Geometry and sizing are evaluated using FHWA projections, scaled for growth when needed, with a strict eye toward not overbuilding, recognizing that the broader network itself contributes to traffic calming.

- Retrofits and upgrades address designs that didn’t age as well or that faced new demands.

- Tradeoffs (footprint, pavement quantities, lane configuration) are weighed on each site to balance performance with multimodal needs.

- Driver-behavior lessons inform each generation of designs so they remain intuitive and self-enforcing.

Beyond Roundabouts: Additional Safety Initiatives

Roundabouts are the cornerstone, but Carmel’s safety strategy extends to the spaces between them:

106th Street and Towne Road Roundabout

- Raised crosswalks temper approach speeds and elevate pedestrian visibility.

- Mid-block crossings with signage or beacons improve safety along longer corridors.

- Multi-use paths connect neighborhoods, schools, parks, and civic destinations, supported by ordinances and standards that maintain quality and access.

- Context-sensitive streetscapes (lane widths, buffers, select on-street parking) reinforce calmer operations where appropriate.

A Personal Path into Engineering

Bradley Pease says engineering has always been about problem-solving and people. “Problem solving… the harder the problem, the more excited I am to try to solve it.”

When a role opened in Carmel, he wanted to be part of the transformation he’d long admired. “I couldn’t wait to join the team that had built… one of the best cities in the country and be more involved.”

He also credits the foundation laid before him. “I stand on the shoulders of giants…” Today, that legacy lets him take on the city’s most complex projects, from challenging multi-use path links to high-volume corridors serving schools, libraries, and neighborhoods, guided by a strong understanding of community needs and future development goals.

Goals for the City and for Pease

With 158 roundabouts in place, the easier conversions are behind them. Carmel is prioritizing intersections with tighter geometry, a constrained right-of-way, higher costs, or sensitive community contexts, while extending multi-use path networks to close critical gaps. Pease is candid about the challenge and his appetite for it, ready to take on “the hardest of the hard problems.”

Looking Ahead

Only a handful of signalized intersections remain under city control: eight city-managed signals, plus six on state-managed roads, and most are slated for future conversion. However, one signal will remain: Main Street & Range Line Road, the historic site tied to Indiana’s early automated signal and marked with a plaque. It anchors the city’s past even as Carmel continues to refine the network that defines its future.

From a one-signal town to 158 ways around, Carmel’s story shows how persistence, innovation, and community focus can reshape a city. We’re proud to work alongside communities like Carmel that place safety at the center of engineering, designing streets that are connected, resilient, and welcoming for everyone.

Graphic provided by the City of Carmel.

Want to Learn More?

Read more about Carmel’s Roundabout Program: https://www.carmel.in.gov/government/departments-services/engineering/roundabouts

Learn more; Listen to ITE Talks Transportation with Jeremy Kashman, City of Carmel:

https://www.spreaker.com/episode/how-carmel-indiana-became-the-roundabout-capital-of-the-united-states–49922954

FHWA Roundabouts: Roundabouts | FHWA

Watch More: Carmel, IN Roundabout Playlist